August 19, 2020

The ultimate meaning to which all stories refer has two faces: the continuity of life, the inevitability of death.

Italo Calvino

I never met Jayelle. I didn’t even know what she looked like. Yet when she suddenly died of a heart attack last month, it hit. Hard. Way harder than I expected from a Twitter follower that I didn’t know in any other capacity.

A few days later, I attempted to find an obituary, something that would give me a more complete picture of the person behind the avatar, but without knowing her last name, it was a fool’s errand. Absent that, I started to piece together what I knew.

We connected through hockey, she was a Penguins fan. I think she was from Pittsburgh originally, although her bio said “Penguins fan in Flyers country,” which probably meant Philadelphia, or at least one of the famous but smaller cities in eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, or Delaware. Allentown? Lancaster? Wilmington? Maybe one of those, maybe none of them. Her wife Katya, who jumped on the account with the tragic news, was Russian and a Red Wings fan, possibly because of her homeland’s well-documented influence on the franchise dating to the 1990s.

She was a huge NASCAR fan as well, and very liberal politically, often changing her Twitter display name to highlight a Trumpian gaffe or the week’s hot issue. Her final change neatly merged the two interests, and to her followers, she’ll always be “Jayelle #IStandWithBubba,” referring to Black NASCAR driver Bubba Wallace and the noose-that-wasn’t found in his garage back in June. She was certainly thrilled with the surprising and progressive moves the sport made in her final weeks, most notably including a ban on Confederate flags at tracks.

Jayelle loved pandas (her profile picture was a drawing of a panda waving a checkered flag), The Simpsons,and The No-Longer-Dixie Chicks, the latter two details filled in after the fact by Katya. I randomly remembered a few days later that she tweeted a ton about The Last Man on Earth when it was on the air. For a moment, I thought about her handle, @GreenEyedLilo, and tried to squeeze something else out of it. Was she Hawaiian? Did she see herself in the character in some other way? Or did she just really like the movie? Ultimately, I had no choice but to let the hopeless ambiguity go.

There was another woman, from my early days on the app. She followed me because of a shared Wings fandom, and we tweeted to each other occasionally. I didn’t know as many of her personal details – she lived somewhere in Macomb County, Michigan and had a special needs son who played goalie. A couple years after our virtual meeting, she mentioned that she had cancer. Some time and a series of Bible verse tweets after that, her account went silent. I suppose there’s enough gray area in the situation to hold out hope for the best absent any confirmation one way or another, but Occam’s Razor would argue otherwise.

Last summer a younger girl, maybe a teenager, passed away. I knew even less about her than I did about @GoalieMom31, but from what I could piece together, she (somewhat obviously) had a lot of health problems and lengthy hospital stays. She had unfulfilled dreams of being able to see the Carolina Hurricanes and Metropolitan Riveters play in person and would sometimes be upset online in the middle of the night, at about the same time as I was whining about some much less significant problem. I did my best to come up with some encouragement when called on to do so, even though I was fully aware that I was throwing a frisbee into, well, her favorite NHL team’s mascot. Then one day, her mother let a bunch of complete strangers know that she was gone.

Really, those situations are the good and bad of this entire digital world rolled up into one place, and laid bare through the most extreme circumstance possible.

The death of a close friend or a family member is a tragedy, while the death of a stranger is a statistic. And for most of human history, those points and the spectrum in between where celebrities, friends of friends, and second grade teachers reside were easy to parse. But how do you process the death of a Twitter follower – someone you can’t say you know know with any degree of intellectual honesty, but who knows things your own parents don’t? Someone whose life, and death, never would’ve entered your orbit in a different generation but represents an algorithm-perfect friend in this one?

I deleted a Twitter account last week. It was both a difficult decision and an easy one.

The difficult part largely had to do with the people that account brought into my life over the last six years. Some have become real-life friends, while plenty of others have entered Jayelle’s sphere. It’s not lost on me that more than one person who will eventually read these words is an “acquaintance,” but only in a sense of the word that didn’t exist 40 years ago.

Still, most or all of those people are safely tucked away in one or more of my other social accounts, so the regret isn’t as much about the past as it is about the future. If I’m not Club Hockey Sandwich, I’m just Kyle. The people who already know Kyle seem okay with him, but there’s not a ton of reason for new people to gravitate his way, beyond some blog posts that nobody outside of his existing circle is likely to know exist.

The easy part? Well, that’s where death re-enters the conversation, although largely in a more metaphorical sense.

Comedic theory is at least as old as Thomas Hobbes, who wrote in Leviathan that people laugh at the misfortune of others due to feeling a “sudden glory,” a relative elevation of their own status. Modern philosophers and psychologists have sewn their own threads into the fabric of our knowledge as well. The University of Colorado’s Peter McGraw found that others getting hurt is funny, provided that no empathy is felt for the victim. At Stanford, William F. Fry forwarded the idea of “play frames,” which largely deal with context – someone tripping and falling on a sidewalk can be funny, but someone falling out of a high rise to their death is not. He also studied the idea of incongruity, the idea that humor is found in breaking expectations.

Those analyses explain a lot about Twitter, which has evolved from its early days of insipid lunch updates to a sort of dystopian open mic free-for-all where people stretch for clout through that one magic joke or dog video that will pull six-figure likes. Too-smart-for-the-room snark is the universal language of the app (and really, pretty much any online territory), and takedowns of anyone who mildly annoys you – celebrities, politicians, brands, random people with a Bad Opinion – preferably in the form of whichever SpongeBob screengrab is circulating at the moment are accepted and even encouraged.

Guns don’t kill people, and neither does Twitter, but they sure make it a lot easier, even if the killing in question is merely a verbal bodybagging.

Wielding the 280-character sickle (well, 140 at the time) was originally the domain of trolls, but soon, the counterattacks came and earned sort of a folk hero status for their purveyors. The Los Angeles Kings were first in the hockey world with their burns of Vancouver and Canada during the 2012 Stanley Cup Playoffs (the initial reaction to the Kings, hilarious in hindsight, was an assumption that someone was having a work-related breakdown and billion variations of “oooh someone’s getting fired”).

But in 2020, a team or league account that doesn’t act that way, at least some of the time, is considered stuffy, and of course, many people and brands in and out of sports have made their reputation through the most blunt form of honesty with a human personality. Wendy’s even flirted with self-parody (and possibly jumping the shark) by using one of those dubious social media-driven “holidays,” National Roast Day, to encourage followers to tweet at them and eat a fresh never frozen clapback.

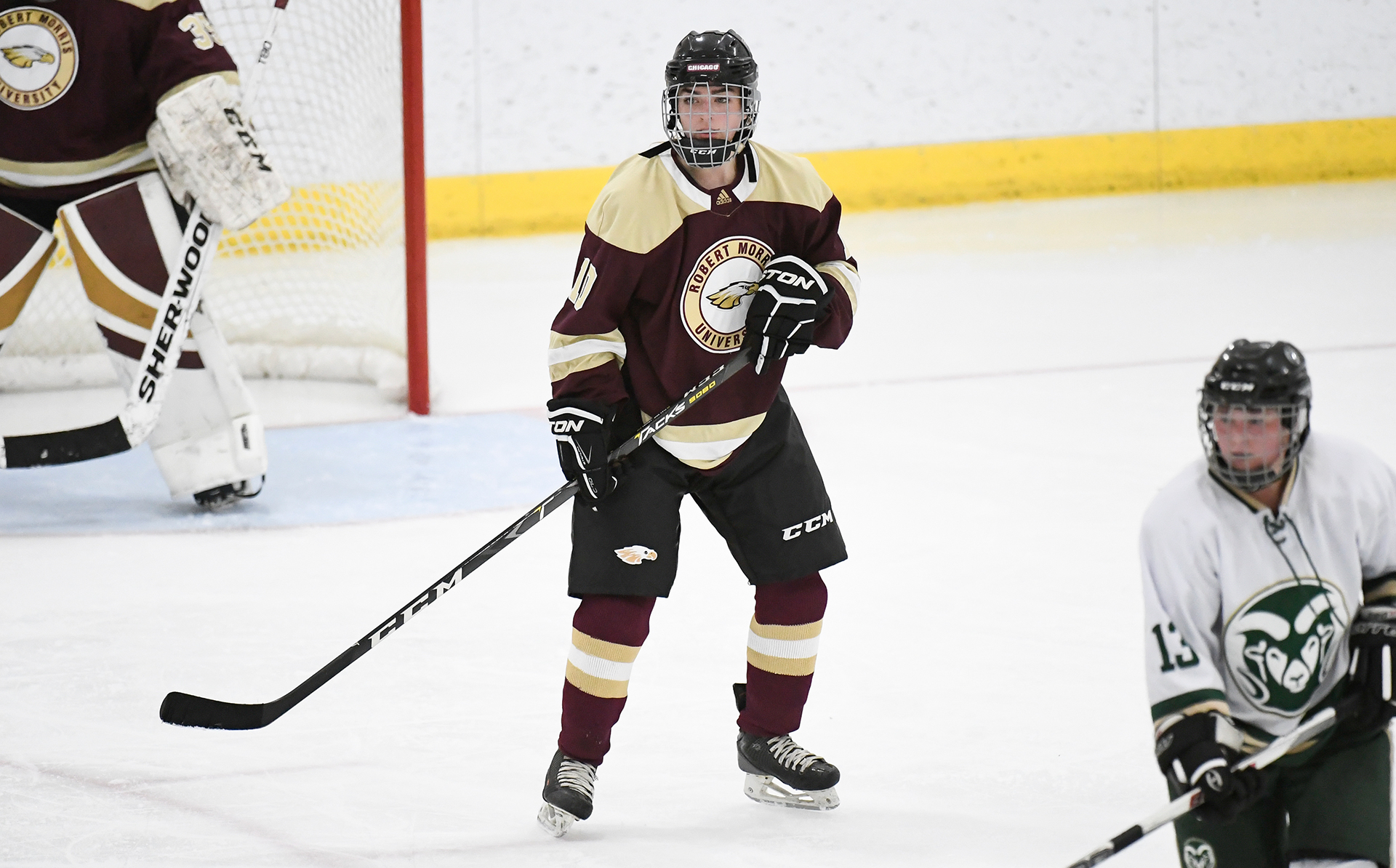

I suppose that’s where I entered the fray. I was never trying to be anything, I made no efforts to expand my personal brand, I just treated my second account as an extension of myself, only with exclusively ACHA women’s hockey content. Sometimes that meant sarcasm and chirps that were never meant to be mean-spirited, 95 percent of the time it didn’t. Nevertheless, I earned a reputation as something of a Twitter hero, a keyboard warrior, a basement dweller, pick your favorite online person pejorative.

The backlash began, just a couple schools at first, followed by a steady trickle. A dad from Delaware yelled at me because I joked about a town named “New City, New York.” Grand Canyon’s team account blocked me because, after noting that they had buildings on campus identified with numbers, I offered to flip them $20 to get my name on one. IUP had half of their roster screaming at me one time because they were using their team account to sling t-shirts for a different club one of their members was in, and I disapproved of it. Central Michigan got annoyed with me asking to go to their recruit skate for some reason, and I still don’t know why Miami stopping liking me after about 2017.

For a long time, I assumed everyone else was the problem. The social trends are clear, I’m not doing anything that hundreds of high-profile accounts aren’t – in fact, I’m pretty tame by some comparisons – my audience is just soft.

That might be partly true; women’s hockey’s audience is much different than what’s typical in the NHL. At the college level, nearly every fan is a parent, a sibling, or a significant other, and those aren’t crowds where negativity has much of a foothold. The outside interest that does pop up, both in and out of the ACHA, largely involves pedestal construction: look at these role models and the legions of young girls they’re inspiring.

Really, it took Jayelle’s death for me to figure it out.

Since the advent of the digital age, we’ve been inclined to separate our acquaintances into groups like “real-life friends” and “internet people,” the unstated part always being that the second group is an off-brand version of the first, a team wearing Athletic Knit playing against Bauer or CCM. But that’s not at all how it works.

The thing is, even though my inventory of Jayelle’s life stopped short of some unknown ideal, it turned out that I actually knew a healthy amount of information. Certainly more than I have on a lot of the people who exist on my real-life periphery, a stock group that always ends up in the same building as me for Easter, Christmas, weddings, and funerals. “Hi, how are you doing, how’s the grind, how about this weather we’re having, see you at the next one.” Jayelle was a step or three beyond that point, despite the fact that I very well could have walked right past her on one of my trips to Philly (if that’s even where she lived) and never realized it.

Human relationships aren’t a dichotomy, they’re a spectrum where locus is merely one consideration, not a rigid category. As unfathomable as the concept might be to anyone before 1990, a certain number of deep conversations and shared interests can outweigh physical proximity and a last name. And in the small world of women’s hockey, almost everyone – even those who have never met in person – is far closer to everyone else than the typical Reply Guy is to a Sara Civian or a Jillian Fisher.

There’s no moral ambiguity to what they’re doing, some rando in Oakleys or represented by a Punisher skull says something mean, and the wisdom of crowds generally gets it right as the media figures and plenty of others pile on.

Meanwhile, everyone in my circle is someone’s teammate, someone’s friend, someone’s daughter. Yet while they may be closer to me than most of Civian’s followers are to her, they’re not close enough to take every comment as intended, to understand my personality and my motives as a friend would. And, oh yeah, they’re still not as close to me on the spectrum as they are to several other segments of my audience. No matter how righteous I may be as an academic exercise, there are consequences to jumping into conflicts, even the most superficial ones about t-shirts.

So began the slow demise of a Twitter account, probably imperceptibly slow to most. Engagement declined, the follower count stagnated, and every other month a new team would have some sort of issue with me. At some point a collision course with a reckoning and a lesson was set, and the death of a friend provided an opportunity for reflection.

If all you’re bringing to life is death, you should probably question your value to the universe. Death is inevitable whether someone brings it or not.

I’m choosing to go home and bring something else for a change.